I'm in the midst of a blog series on AI-related ideology and politics. In Part I, I went over some foundational concepts that many players in the AI space are working from. In this Part II I will be introducing you to those players.

As an AI hobbyist, I've been aware of all these movements for some time, and have interacted with them in a peripheral way (e.g. reading their blog articles). But I have not become a member of, worked alongside, or fought against any of these communities. So what I write here is some combination of shallow first-hand knowledge, and research.

Rationalists

When you think of a "rational person," you might picture someone devoted to principles of logical or scientific thinking. If you internet-search "Rationalist," you'll see references to a category of philosopher that includes René Descartes and Immanuel Kant. These kinds of Rationalists are not our present concern; the movement I am about to describe is both more modern and more specific.

The Rationalists are a community that clusters around a few key figures (Eliezer Yudkowsky, Scott Alexander) and a few key websites (LessWrong and Slate Star Codex). Their self-description [1] on the LessWrong wiki doesn't include any clear mission statement; however, it has been said that they formed around the idea of making humanity - or at least a leading subset of humanity - smarter and more discerning [2][3][4]. They're a movement to develop and promote the modes of thinking they see as most rational. Rationalist hobbies include pondering thought experiments, trying to identify and counter cognitive biases, and betting on prediction markets. [5]

Rationalists define "rationality" as "the art of thinking in ways that result in accurate beliefs and good decisions." [6] They strongly favor Bayesian thinking as one of these ways. [7][8] My quick dirty description of Bayesianism is "I will base my beliefs on the preponderance of evidence I have; when I get new evidence, I will update my beliefs accordingly." At least, that's how the average person would probably implement it. At its most basic level, it implies a devotion to objective truth discovered empirically. In the hands of Rationalists, this idea can get very formal. They'll try to compute actual numbers for the probability that their opinions are true. On the "good decisions" side of the coin, they love applying Game Theory everywhere they can. Are these techniques truly useful, or are they just a form of over-analysis, prompted by a yearning for more accuracy than we can practically attain? I frankly don't know. My reaction whenever I glance at Rationalist studies of "thinking better" is "that sounds like it might be really cool, actually, but I don't have time for it right now; my existing methods of reasoning seem to be working okay."

There is no list of mandatory opinions one must have to be allowed in the Rationalist "club"; in fact, it has drawn criticism for being so invested in open-mindedness and free speech that it will entertain some very unsavory folks. [9] A demographic survey conducted within the community suggests that it is moderately cosmopolitan (with about 55% of its members in the USA), skews heavily male and white, leans left politically (but with a pretty high proportion of libertarians), and is more than 80% atheist/agnostic. [10] That last one interests me as a possible originating factor for the Rationalists' powerful interest in X-risks. If one doesn't believe in any sort of Higher Power(s) balancing the universe, one is naturally more likely to fear the destruction of the whole biosphere by some humans' chance mistake. The survey was taken almost ten years ago, so it is always possible the demographics have shifted since.

What does any of this have to do with AI? Well, AI safety - and in particular, the mitigation of AI X-risk - turns out to be one of the Rationalists' special-interest projects. Rationalists overlap heavily with the Existential Risk Guardians or Doomers, whom we'll look at soon.

Post-Rationalists (Postrats)

These are people who were once Rationalists, but migrated away from Rationalism for whatever reason, and formed their own diaspora community. Maybe they tired of the large physical materialist presence among Rationalists, and got more interested in spiritual or occult practices. Or maybe they found that some aspects of the movement were unhealthy for them. Maybe some of them are just Rationalists trying to be better (or "punker") than the other Rationalists. [11][12]

Postrats don't necessarily lose their interest in AI once they leave the Rationalist community, though their departure may involve releasing themselves from an obsessive focus on AI safety. So they form a related faction in the AI space. I think of them as a wilder, woolier, but also more mellow branch off the Rationalists.

Existential Risk Guardians (Doomers, Yuddites, Decelerationists, or Safteyists)

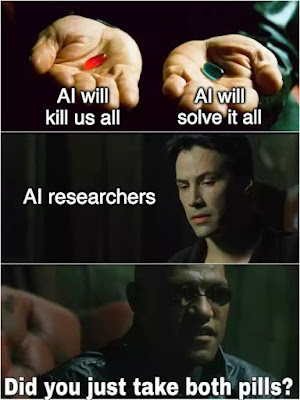

The term "Yuddite" denotes these people as followers of Yudkowsky, already mentioned as a founder of the Rationalist movement. "Existential Risk Guardians" is my own invented attempt to name them as they might see themselves; "Doomer" is the most common term I've seen, but is perhaps slightly pejorative. Still, I'll be using it for the rest of these articles, to avoid confusion. They're called "Doomers" because they expect continued development of AI under present conditions to bring us doom. Horrible, total, kill-all-humans doom. And they're the lonely few who properly comprehend the threat and are struggling to prevent it.

The Doomer argument deserves a proper examination, so I'm planning to go over it in detail in an upcoming article. The quickest summary I can give here is 1) AI will eventually become agentive and much smarter than we are, 2) it is far more likely than not to have bizarre goals which compete with classic human goals like "living and breathing in a functioning ecosystem," 3) it will recognize that humans pose a risk to its goals and the most effective course of action is to wipe us out, and 4) by the power of its superior intelligence, it will be unstoppable. To make matters worse, it's possible that #1 will happen in a sudden and unexpected manner, like a chain reaction, when someone drops the last necessary algorithms into a previously harmless system.

That nightmare scenario can be negated by undercutting point #2: instead of creating an ASI with anti-human goals, create one with goals that more or less match our own. Solve the Alignment Problem. The Doomer position is that we, as humans and AI developers, currently have no solid idea of how to do this, and are careening heedlessly toward a future in which we're all at the mercy of an insane machine god. Yudkowsky himself is SO terrified that his rhetoric has shifted from (I paraphrase) "we must prevent this possibility" toward "we are quite likely going to die." [13]

The genuine fear produced by this idea leads some Doomers to work obsessively, either on research aimed at solving the Alignment Problem, or on public relations to recruit more workers and money for solving it. The task of preventing AI doom becomes life-absorbing. It has spawned a number of organizations whose purpose is reducing AI X-risk, including MIRI (the Machine Intelligence Research Institute), the Center for AI Safety, the Future of Life Institute, and OpenAI. Yes, really: at its beginning, OpenAI was a fully non-profit organization whose stated goal was to develop safe AI that would "benefit humanity," in a transparent, democratic sort of way. People would donate to OpenAI as if it were a charity. [14] Then it got funding from Microsoft and began keeping its inventions under wraps and releasing them as proprietary commercial products. This double nature helps explain some recent tensions within the organization. [15]

Doomers tend to push for slower and more accountable AI development, hence the related name "Decelerationists." The competitive nature of technological progress at both the corporate and national levels stokes their fear; is there any place for safety concerns in the mad rush to invent AGI before somebody else does? They look for hope in cooperative agreements to slow (or shut) everything down. But in the current landscape, these do not seem forthcoming.

Effective Altruists

Effective Altruism is a close cousin of Rationalism that tries to apply Rationalist principles to world-improving action. It was birthed as a movement encouraging well-off people to 1) actually give meaningful amounts of money to charitable work, and 2) assign that money to the organizations or causes that produce maximum benefit per dollar. I dare say most people like the idea of giving to reputable, efficient organizations, to ensure their money is not being wasted; core EA is merely a strict or obsessive version of that. Giving becomes a numerical problem to be solved in accordance with unprejudiced principles: you put your money where it saves the most lives or relieves the greatest suffering, no matter whether those helped are from your own community or country, whether they look or think the way you do, etc. [16]

In my opinion, there is little to criticize about this central nugget of the EA ideal. One might argue that Effective Altruists overestimate their ability to define and measure "effectiveness," becoming too confident that their favored causes are the best. But at heart, they're people trying to do the most good possible with limited resources. Favorite projects among early EAs were things like malaria prevention in developing countries, and these continue to be a major feature of the movement. [17] Led by its rejection of prejudice, the EA community also crossed species lines and eventually developed a strong animal welfare focus. This is all very nice.

Then why is EA controversial?

A stereotypical Effective Altruist defines altruism along utilitarian consequentialist lines. EAs take pains to note that utilitarianism is not a mandatory component of EA - you can use EA ideas in service of other ethical systems [18]. But EA does align well with a utilitarian ethos: "Out of all communities, the effective altruism movement comes closest to applying core utilitarian ideas and values to the real world." [19][20] The broad overlap with the Rationalist community, in which consequentialism is the dominant moral philosophy per the community survey [21], also suggests that a lot of people in the EA space happen to be working from it. My point being that non-utilitarians might find some EA-community ideas of what counts as "the most good" suboptimal. The way EAs interpret utilitarianism has led occasionally to weird, unpalatable conclusions, like "torturing one person for fifty years would be okay if it prevented a sufficiently enormous number of people from getting dust in their eye." [22] EAs have also played numbers games on the animal welfare front - for instance, emphasizing that eating one cow causes less suffering than eating a bunch of chickens, instead of centering every animal's individual interest in not being killed. [23]

Further controversies are added by blendings of the EA movement with other ideologies on this list - each of which has its own ideas of "greatest need" and "maximum benefit" that it can impose on EA's notion of "effectiveness." If you take the real Doomers seriously, solving the AI Alignment Problem (to prevent total human extinction) starts to look more important than saving a few million people from disease or privation. These notions redirected some EA dollars and time from overt humanitarian efforts, toward AI development and AI safety research initiatives. [24][25]

EA has also acquired a black eye because, in a terrible irony for a charitable movement, it contains an avenue for corruption by the love of money. EA has sometimes included the idea that, in order to give more, you should make more: as much as possible, in fact. Forgo a career that's socially beneficial or directly productive, to take up business or finance and rake in the cash. [26] And in at least one high-profile case, this went all the way to illegal activity. Sam Bankman-Fried, currently serving jail time for fraud, is the EA movement's most widely publicized failure. I've never seen signs that the movement as a whole condones or advocates fraud, but Bankman-Fried's fall illustrates the potential for things to go wrong within an EA framework. EA organizations have been trying to distance the movement from both Bankman-Fried and "earning to give" in general. [27]

Longtermists

In its simplest and most general form, longtermism is the idea that we have ethical obligations to future generations - to living beings who do not yet exist - and we should avoid doing anything now which is liable to ruin their lives then. Life on earth could continue for many generations more, so this obligation extends very far into the future, and compels us to engage in long-term thinking. [28]

|

| An exponential curve, illustrative of growth toward a singularity. |

In its extreme form, longtermism supposes that the future human population will be immensely large compared to the current one (remember the Cosmic Endowment?). Therefore, the future matters immensely more than the present. Combine this mode of thought with certain ethics, and you get an ideology in which practically any sort of suffering is tolerable in the present IF it is projected to guarantee, hasten, or improve the existence of these oodles of hypothetical future people. Why make sure the comparatively insignificant people living today have clean water and food when you could be donating to technical research initiatives that will earn you the gratitude of quadrillions (in theory, someday, somewhere)? Why even worry about risks that might destroy 50% of Earth's current tiny population, when complete human extinction (which would terminate the path to that glorious future) is on the table? [29][30]

Even if you feel sympathy with the underlying reasoning here, it should be evident how it can be abused. The people of the future cannot speak for themselves; we don't really know what will help them. We can only prognosticate. And with enough effort, prognostications can be made to say almost anything one likes. Longtermism has been criticized for conveniently funneling "charity" money toward billionaire pet projects. Combined with Effective Altruism, it pushes funding toward initiatives aimed at "saving the future" from threats like unsafe AI, and ensuring that we populate our light cone.

E/ACC and Techno-optimists

E/ACC is short for "effective accelerationism" (a play on "effective altruism" and a sign that this faction is setting itself up in a kind of parallel opposition thereto). The core idea behind E/ACC is that we should throw ourselves into advancing new technology in general, and AI development in particular, with all possible speed. There are at least two major motives involved.

First, the humanity-forward motive. Technological development has been, and will continue to be, responsible for dramatic improvements in lifespan, health, and well-being. In fact, holding back the pace of development for any reason is a crime against humanity. Tech saves lives, and anyone who resists it is, in effect, killing people. [31]

Second, the "path of evolution" motive. This brand of E/ACC seems to worship the process of advancement itself, independent of any benefits it might have for us or our biological descendants. It envisions humans being completely replaced by more advanced forms of "life," and in fact welcomes this. To an E/ACC of this type, extinction is just part of the natural order and not anything to moan about. [32] The sole measure of success is not love, happiness, or even reproductive fitness, but rather "energy production and consumption." [33] Though E/ACC as a named movement seems fairly new, the idea that it could be a good thing for AI to supplant humans goes back a long way ... at least as far as Hans Moravec, who wrote in 1988 that our "mind children" would eventually render embodied humans obsolete. [34]

It's possible that both motives coexist in some E/ACC adherents, with benefit to humanity as a step on the road to our eventual replacement by our artificial progeny. E/ACC also seems correlated with preferences for other kinds of growth: natalism ("everyone have more babies!") and limitless economic expansion. E/ACC adherents like to merge technology and capitalism into the term "technocapital." [35]

Anticipation of the Technological Singularity is important to the movement. For humanity-forward E/ACC, it creates a secular salvation narrative with AI at its center. It also functions as a kind of eschaton for the "path of evolution" branch, but they emphasize its inevitability, without as much regard to whether it is good or bad for anyone alive at the moment.

When E/ACC members acknowledge safety concerns at all, their classic response is that the best way to make a technology safe is to develop it speedily, discover its dangers through experience, and negate them with more technology. Basically, they think we should all learn that the stove is hot by touching it.

I would love to describe "techno-optimism" as a less extreme affinity for technology that I could even, perhaps, apply to myself. But I have to be careful, because E/ACC people have started appropriating this term, most notably in "The Techno-Optimist Manifesto" by Marc Andreessen. [36] This document contains a certain amount of good material about how technology has eased the human condition, alongside such frothing nonsense as "Our present society has been subjected to a mass demoralization campaign for six decades – against technology and against life – under varying names like ... “sustainability”, ... “social responsibility”, “stakeholder capitalism”, “Precautionary Principle”, “trust and safety”, “tech ethics”, “risk management” ..."

Excuse me? Risk management, trust and safety, ethics, etc. are part and parcel of good engineering, the kind that produces tech which truly serves the end user. Irresponsible and unsustainable development isn't just immediately harmful - it's also a great way to paint yourself into a corner from which you can't develop further. [37]

The E/ACC people and the Rationalist/EA/Doomer factions are, at least notionally, in direct opposition. Longtermism seems more commonly associated with EAs/Doomers, but E/ACCs share the tendency to focus toward the future; they just don't demand that the future be populated by humans, necessarily.

|

| Doomer and E/ACC aligned accounts sniping at each other on Twitter. Originals: https://twitter.com/AISafetyMemes/status/1733881537156780112 and https://twitter.com/bayeslord/status/1755447720666444235 |

Mundane AI Ethics Advocates

People in this group are worried about AI being poorly designed or misused in undramatic, everyday ways that fall far short of causing human extinction, but still do harm or exacerbate existing power imbalances. And they generally concern themselves with the narrow, limited AI being deployed right now - not hypothetical future AGI or ASI. Examples of this faction's favorite issues include prejudiced automated decision-making, copyright violations, privacy violations, and misinformation.

Prominent figures that I would assign to this faction include Emily Bender, a linguistics professor at the University of Washington [38] and Timnit Gebru, former co-lead of the ethical AI team at Google [39].

These are obvious opponents for E/ACC, since E/ACC scoffs at ethics and safety regulations, and any claim that the latest tech could be causing more harm than good. But they also end up fighting with the Doomers. Mundane AI Ethics Advocates often view existential risk as a fantasy that sucks resources away from real and immediate AI problems, and provides an excuse to concentrate power among an elite group of "safety researchers."

Capitalists

In this category I'm putting everyone who has no real interest in saving humanity either from or with AI, but does have a grand interest in making money off it. I surmise this includes the old guard tech companies (Microsoft, Google, Meta, Amazon, Apple), as well as a variety of people in the startup and venture capital ecosystem. This faction's focus is on getting AI tools to market as fast as possible, convincing consumers to adopt them, and limiting competition. Though they don't necessarily care about any of the ideologies that animate the other factions, they can still invoke them if it increases public interest and helps to sell their product.

E/ACC are the natural allies for this group, but Doomer rhetoric can also be useful to Capitalists. They could use existential risk as an excuse to limit AI development to a list of approved and licensed organizations, regulating smaller companies and free open-source software (FOSS) efforts off the playing field. Watch for attempts at regulatory capture whenever you see a corporation touting how dangerous their own product is.

Scientists

This group's dominant motive is curiosity. They just want to understand all the new AI tools coming out, and they think an open and free exhange of information would benefit everyone the most. They may also harbor concerns about democracy and the concentration of AI power in a too-small number of hands. In this group I'm including the FOSS community and its adherents.

This faction is annoyed by major AI developers' insistence on keeping models, training data sets, and other materials under a veil of proprietary secrecy - whether for safety or just for intellectual property protection. Meanwhile, it is busily doing its best to challenge corporate products with its own open and public models.

Members of this faction can overlap with several of the others.

TESCREAL

This is an umbrella term which encompasses several ideologies I've already gone over. TESCREAL stands for: Transhumanism, Extropianism, Singularitarianism, Cosmism, Rationalism, Effective Altruism, Longtermism. The acyronym was invented by Èmile P. Torres and Timnit Gebru [39] as a way to talk about this basket of ideas and their common roots.

I haven't devoted a separate section to Transhumanism because I hope my readers will have heard of it before. It's the idea that technology can radically transform the human condition for the better, especially by modifying human embodiment (via cyborg implants, gene therapy, aging reversal, or mind uploading). Extropianism was just a branch or subculture of Transhumanism, which now appears to be extinct or folded into the later movements. I touched on Singularitarianism in Part I of this article series; you can also think of E/ACC as more recent descendants of its optimistic wing.

I don't know a whole lot about Cosmism. It's an old Russian ideology that promoted the exploration and colonization of space, the discovery of ways to bring back the dead, and perhaps some geoengineering. [41] I haven't personally encountered it in my circles, but it could be part of the heritage behind ideas like the Cosmic Endowment. A modern variant of it has been championed by Ben Goertzel (the person who popularized the term "AGI"). This version of Cosmism seems to be Goertzel's own invention, but "The previous users of the term 'Cosmism' held views quite sympathetic to my own, so classifying my own perspective as an early 21st century species of Cosmism seems perfectly appropriate." [42]

The TESCREAL basket is a clutter of diverse ideologies, some of which are even diametrically opposed (utopian Singularitarianism vs. Doomer EA). Their common thread is their birth out of Transhumanist ideas, and shared goals like attaining immortality and spreading human-originated civilization throughout the cosmos.

Conclusion

The above is not meant as an exhaustive list. There are certainly people in the AI field who don't fit neatly into any of those factions or trends - including yours truly. I probably have the greatest sympathy for the Mundane AI Ethics Advocates, but I'm not really working in that space, so I don't claim membership.

And in case it wasn't clear from my writing in each section, I'm not trying to paint any of the factions as uniformly bad or good. Several of them have a reasonable core idea that is twisted or amplified to madness by a subset of faction members. But this subset does have influence or prominence in the faction, and therefore can't necessarily be dismissed as an unrepresentative "lunatic fringe."

In Part III, I'll look more closely at some of the implications and dangers of this political landscape.

[1] "Rationalist Movement." Lesswrong Wiki. https://www.lesswrong.com/tag/rationalist-movement

[2] "Developing clear thinking for the sake of humanity's future" is the tagline of the Center For Applied Rationality. Displayed on https://rationality.org/, accessed February 2, 2024.

[3] "Because realizing the utopian visions above will require a lot of really “smart” people doing really “smart” things, we must optimize our “smartness.” This is what Rationalism is all about ..." Torres, Èmile P. "The Acronym Behind Our Wildest AI Dreams and Nightmares." TruthDig. https://www.truthdig.com/articles/the-acronym-behind-our-wildest-ai-dreams-and-nightmares/

[4] "The chipper, distinctly liberal optimism of rationalist culture that defines so much of Silicon Valley ideology — that intelligent people, using the right epistemic tools, can think better, and save the world by doing so ..." Burton, Tara Isabella. "Rational Magic." The New Atlantis. https://www.thenewatlantis.com/publications/rational-magic

[5] Roose, Kevin. "The Wager that Betting Can Change the World." The New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/2023/10/08/technology/prediction-markets-manifold-manifest.html

[6] "Rationality." Lesswrong Wiki. https://www.lesswrong.com/tag/rationality

[7] Kaznatcheev, Artem. "Rationality, the Bayesian mind and their limits." Theory, Evolution, and Games Group blog. https://egtheory.wordpress.com/2019/09/07/bayesian-mind/

[8] Soja, Kat (Kaj_Sotala). "What is Bayesianism?" Lesswrong. https://www.lesswrong.com/posts/AN2cBr6xKWCB8dRQG/what-is-bayesianism

[9] Ozymandias. "Divisions within the LW-Sphere." Thing of Things blog. https://thingofthings.wordpress.com/2015/05/07/divisions-within-the-lw-sphere/

[10] Alexander, Scott. "2014 Survey Results." Lesswrong. https://www.lesswrong.com/posts/YAkpzvjC768Jm2TYb/2014-survey-results

[11] Burton, "Rational Magic."

[12] Falkovich, Jacob. "Explaining the Twitter Postrat Scene." Lesswrong. https://www.lesswrong.com/posts/rtM3jFaoQn3eoAiPh/explaining-the-twitter-postrat-scene

[13] Do note that this is an April Fools' Day post. However, the concluding section stops short of unambiguously confirming that it is a joke. It seems intended as a hyperbolic version of Yudkowsky's real views. Yudkowsky, Eliezer. "MIRI announces new 'Death With Dignity' strategy." Lesswrong. https://www.lesswrong.com/posts/j9Q8bRmwCgXRYAgcJ/miri-announces-new-death-with-dignity-strategy

[14] Harris, Mark. "Elon Musk used to say he put $100M in OpenAI, but now it’s $50M: Here are the receipts." TechCrunch. https://techcrunch.com/2023/05/17/elon-musk-used-to-say-he-put-100m-in-openai-but-now-its-50m-here-are-the-receipts/

[15] Allyn, Bobby. "How OpenAI's origins explain the Sam Altman drama." NPR. https://www.npr.org/2023/11/24/1215015362/chatgpt-openai-sam-altman-fired-explained

[16] "It’s common to say that charity begins at home, but in effective altruism, charity begins where we can help the most. And this often means focusing on the people who are most neglected by the current system – which is often those who are more distant from us." Centre for Effective Altruism. "What is effective altruism?" Effective Altruism website. https://www.effectivealtruism.org/articles/introduction-to-effective-altruism

[17] Mather, Rob. "Against Malaria Foundation: What we do, How we do it, and the Challenges." Transcript of a talk given at EA Global 2018: London, hosted on the Effective Altruism website. https://www.effectivealtruism.org/articles/ea-global-2018-amf-rob-mather

[18] Centre for Effective Altruism. "Frequently Asked Questions and Common Objections." Effective Altruism website. https://www.effectivealtruism.org/faqs-criticism-objections

[19] MacAskill, W. and Meissner, D. "Acting on Utilitarianism." In R.Y. Chappell, D. Meissner, and W. MacAskill (eds.), An Introduction to Utilitarianism. Hosted at utilitarianism.net. https://utilitarianism.net/acting-on-utilitarianism/#effective-altruism

[20] Pearlman, Savannah. "Is Effective Altruism Inherently Utilitarian?" American Philosophical Association blog. https://blog.apaonline.org/2021/03/29/is-effective-altruism-inherently-utilitarian/

[21] Alexander, "2014 Survey Results."

[22] The main article here only propounds the thought experiment. You need to check the comments for Yudkowsky's answer, which is "I do think that TORTURE is the obvious option, and I think the main instinct behind SPECKS is scope insensitivity." And yes, Yudkowsky appears to be influential in the EA movement too. Yudkowsky, Eliezer. "Torture vs. Dust Specks." Lesswrong. https://www.lesswrong.com/posts/3wYTFWY3LKQCnAptN/torture-vs-dust-specks

[23] Matthews, Dylan. "Why eating eggs causes more suffering than eating beef." Vox. https://www.vox.com/2015/7/31/9067651/eggs-chicken-effective-altruism

[24] Todd, Benjamin. "How are resources in effective altruism allocated across issues?" 80,000 Hours. https://80000hours.org/2021/08/effective-altruism-allocation-resources-cause-areas/

[25] Lewis-Kraus, Gideon. "The Reluctant Prophet of Effective Altruism." The New Yorker. https://www.newyorker.com/magazine/2022/08/15/the-reluctant-prophet-of-effective-altruism

[26] "Earning to Give." Effective Altruism forum/wiki. https://forum.effectivealtruism.org/topics/earning-to-give

[27] "Our mistakes." See sections "Our content about FTX and Sam Bankman-Fried," and "We let ourselves become too closely associated with earning to give." 80,000 Hours. https://80000hours.org/about/credibility/evaluations/mistakes/

[28] MacAskill, William. "Longtermism." William MacAskill's personal website. https://www.williammacaskill.com/longtermism

[29] Samuel, Sigal. "Effective altruism’s most controversial idea." Vox. https://www.vox.com/future-perfect/23298870/effective-altruism-longtermism-will-macaskill-future

[30] Torres, Èmile P. "Against Longtermism." Aeon. https://aeon.co/essays/why-longtermism-is-the-worlds-most-dangerous-secular-credo

[31] "But an overabundance of caution results in infinite loops of the regulatory apparatus directly killing people through opportunity costs in medicine, infrastructure, and other unrealized technological gains." Asparouhova, Nadia, and @bayeslord. "The Ethos of the Divine Age." Pirate Wires. https://www.piratewires.com/p/ethos-divine-age

[32] "Effective Acceleration means accepting the future." Effective Acceleration explainer website, which purports to be the front of a "leaderless" movement and therefore lists no authors. https://effectiveacceleration.tech/

[33] Baker-White, Emily. "Who Is @BasedBeffJezos, The Leader Of The Tech Elite’s ‘E/Acc’ Movement?" https://www.forbes.com/sites/emilybaker-white/2023/12/01/who-is-basedbeffjezos-the-leader-of-effective-accelerationism-eacc/?sh=40f7f3bc7a13

[34] Halavais, Alexander. "Hans Moravec, Canadian computer scientist." Encylopedia Britannica online. https://www.britannica.com/biography/Hans-Moravec

[35] Ruiz, Santi. "Technocapital Is Eating My Brains." Regress Studies blog. https://regressstudies.substack.com/p/technocapital-is-eating-my-brains

[36] Andreessen, Marc. "The Techno-Optimist Manifesto." A16Z. https://a16z.com/the-techno-optimist-manifesto/

[37] Masnick, Mike. "New Year’s Message: Moving Fast And Breaking Things Is The Opposite Of Tech Optimism." TechDirt. https://www.techdirt.com/2023/12/29/new-years-message-moving-fast-and-breaking-things-is-the-opposite-of-tech-optimism/

[38] Hanna, Alex, and Bender, Emily M. "AI Causes Real Harm. Let’s Focus on That over the End-of-Humanity Hype." Scientific American. https://www.scientificamerican.com/article/we-need-to-focus-on-ais-real-harms-not-imaginary-existential-risks/

[39] Harris, John. "‘There was all sorts of toxic behaviour’: Timnit Gebru on her sacking by Google, AI’s dangers and big tech’s biases." The Guardian. https://www.theguardian.com/lifeandstyle/2023/may/22/there-was-all-sorts-of-toxic-behaviour-timnit-gebru-on-her-sacking-by-google-ais-dangers-and-big-techs-biases

[40] Torres, "The Acronym Behind Our Wildest AI Dreams and Nightmares."

[41] Ramm, Benjamin. "Cosmism: Russia's religion for the rocket age." BBC. https://www.bbc.com/future/article/20210420-cosmism-russias-religion-for-the-rocket-age

[42] Goertzel, Ben. "A Cosmist Manifesto." Humanity+ Press, 2010. https://goertzel.org/CosmistManifesto_July2010.pdf