|

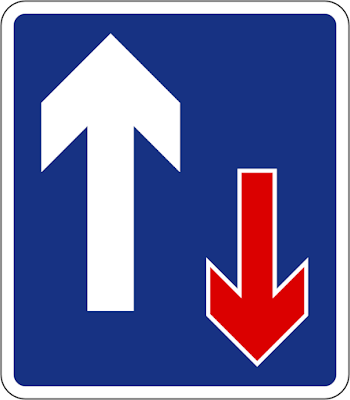

| The goal of a moral argument is to show someone that their behavior is inconsistent with core moral principles you both share. Someone who doesn't share your core morals can't be argued into agreeing with you. So giving AIs compatible moral standards is pretty important. Comic from Freefall by Mark Stanley. |

Adventures in robotics and AI on a shoestring budget. SFF fiction and occasional video game appreciation.

Thursday, March 24, 2022

Acuitas Diary #47

Saturday, March 12, 2022

Primordia: Or, Why Do I Build Things?

I haven't written a video game blog in a while, and today, I finally want to talk about Primordia, by Wormwood Studios. It's an older game, but one that's very important to me, and I've held off writing about it for so long because ... I guess it seemed difficult. I really wanted to get the article right, and now it's time.

For those not familiar with my video game posts, they aren't really reviews. They're stories about the power of art: how something I played taught me a lesson or left a mark on my life. There will be spoilers, so if you want to try the game for yourself with a fresh mind, go play it before you read this.

Primordia is a “point-and-click adventure game” about robots living in a post-apocalyptic world - possibly future Earth, though this is not explicit. Biological life appears extinct; tiny machines even substitute for insects. But the robots recall their absent creators, the humans, though imperfect historical records have distorted their perspective. In most robots' minds, the whole race has contracted to a monolithic entity called "Man," imagined as "a big robot" or "the perfect machine." In the Primordium - the time of creation - Man built all other machines, then gave them the planet as an inheritance and departed. Some robots (including Horatio, the player character) religiously venerate Man. Others are more indifferent, or believe that Man never really existed (they even have a machine theory of evolution to back this up).

|

| Horatio (left) and Crispin. |

Life for these robots is a bleak struggle for survival. Like abandoned children, they linger among the wreckage of human civilization without fully understanding how to maintain it. They slowly drain the power sources their creators left behind, and repair themselves with parts from already-dead machines. Some have broken down, some have developed AI versions of psychosis, and some have started victimizing other robots.

Horatio lives in the dunes, an isolated

scavenger. He's an android; but beyond imaging Man physically, he

believes that Man, the builder, gave him the purpose of building.

This belief animates everything he does. In addition to crafting what

he needs to maintain his existence, Horatio creates spontaneously. He

can't remember any particular reason why he should restore function

to the crashed airship in the desert, but for him it's an act of

reverence. He's even made himself a smaller companion named Crispin,

who follows him everywhere and calls him “boss.” Events force

Horatio to leave his home in the desert and enter one of the ancient

cities, where he must match wits with Metromind, the powerful

mainframe AI who rules the place.

|

| As a person who went on a walk this very day and came home with somebody's discarded rice cooker ... I love these characters |

The plot is solid no matter who you are ... but here's how this game got me. I am an (admittedly not professional) roboticist. Whenever the robots in Primordia said anything about "Man," I thought, "Oh, they're totally talking about me." And I started internalizing it. I accepted Horatio's loyalty. I laughed at Crispin's agnosticism. I pondered Metromind's disdain for me. Ahahahaha woops!

At some point after I effectively became a character in the game, I realized I'd been cast as the absent creator. At one point, Crispin asks Horatio why their world is so messed up, and Horatio comes back with the sort of answer I'd expect from a pastor: he argues that Man built the world well, but then the robots began to violate their intended functions, imbalancing and damaging everything. He is both right and wrong: the humans in this setting also share some blame. The inhabitants of the rival city-states were more interested in killing each other than in caring for what they'd built.

Horatio cannot pray; everything Man

gave him, he already has, and now he must face his troubles alone. By

the time Primordia's story begins, he has already re-versioned

himself and wiped his episodic memory four times ... one of the game

endings suggests that he did this to seal away past trauma. And he's

probably got one of the strongest senses of agency in the game. The other robots are largely helpless, trapped in decaying systems that they

hope a dominant AI like Metromind will fix.

|

| One page from the "scripture" Horatio carries. |

And the first weird thing that happened to me, the player, was that this huuuurrrt. It hurt to a bizarre degree. My inability to apologize to Horatio on behalf of humanity, or make anything up to him at all, left me rather miserable ... even after I wound up the game with one of the better endings. Yeah, he managed to come through okay, but some miserable roboticist I am. Why wasn't I there?

Speaking of endings, the game has a lot of branching options. I re-ran the final scenes a bunch of times to explore them. And for whatever reason ... perhaps to ease my angst ... I started daydreaming and inserting myself. If I confronted Metromind, what would I do? She has a memory that goes back to the time of real humans, and as it turns out, she murdered all the humans in her city. She's one of the few characters with a classic "rebellious AI" mindset: she decided that those who made her were weak and inferior, and she could run the city better. (And then, having been designed only to run the subway system, she found herself in way over her ... monitor?) Metromind also has a primary henchman called Scraper. If you're smart about how you play, you can have Horatio opt to either kill Scraper or not.

When I imagine myself there at the climax, my emotional response to Metromind is ... strangely calm. She killed many of my species and would probably like to kill me, but I almost don't mind; I am above minding. We made her, after all. She can sneer at me or hate me if she wants; I'm far too important to be bothered.

|

| Scraper plots nefarious deeds |

The only thing that draws anger out of me is the ending in which Horatio gets killed in a fight over the power core. It's not even the fact that they kill him; it's what Metromind says afterward. She directs Scraper to "Take him out to the dunes ... with the rest of the scrap." This makes me want to flip my computer table over and roar, "HORATIO. IS NOT. SCRAP!" Being devalued myself is tolerable. Seeing Horatio devalued is, somehow, not.

I don't like the ending in which he mind-merges with Metromind to help her run the city, either. It could be viewed as positive, in some ways. But watching Horatio's individual personality get subsumed into this union is unexpectedly horrifying. Again, I feel curiously insulted. "Horatio! Somebody gave you that individuality! Don't dissolve it, you haven't any right!"

I wasn't observing myself too well; it took me a while to become aware of the pattern. And when I woke up and realized how I was behaving, I was startled. I was roleplaying some kind of benevolent creator goddess. And the revelatory thing about this was that it came so naturally, I didn't even notice. Some of my responses were a mite counter-intuitive, yet there was no effort involved. It was as if I had latent instincts that had been waiting for this exact scenario, and they quietly switched on. I was left looking at myself like an unfamiliar person and asking “How did I do that?”

What I took away is that I seem to have my own bit of innate core code for relating to artificial life. Which if you think about it is ... weird. Nothing like the robots in Primordia exists yet. How long have we had anything that even vaguely resembles them? For what fraction of human history has interaction with robots been an issue? Perhaps one could claim that I was working from a misplaced parental instinct, but it feels more particular than that. So where did I get it? Why would I react this way to the things I build? Why, indeed, do I build things?

I'm leaving that one as an exercise for the reader! Not to be purposely mysterious, but I think the answer will land better if you can see it for yourself. The bottom line is that I know things about my work, and about me, that I did not know before I took my tour through Primordia.

If you play it, what might you learn?