Note: this is part 2 in my response to the book Robotic Persons, by Joshua Smith, which attempts to present an evangelical Christian perspective on AI rights and personhood. Please read my introductory book review if you haven't already.

One of the key arguments in Smith's book is that the idea of the soul is important to the Christian concept of personhood and natural rights. He further alleges that robots and other AIs cannot have souls, and therefore can never attain natural rights or true personhood. Although I do agree with his first point, I found the support for his second point to be quite weak. To definitively state that a robot can never have a soul as Christians understand souls, we would need a solid idea of what souls *are* and how they are conferred on humans. The Bible leaves room for some speculation on both topics.

A soul is presumed to be, in some way, the essence or core of a person. It is also commonly associated with immortality and the possibility of existence beyond bodily death (though some Christians have held that the soul cannot operate without the body and is unconscious, perhaps even non-existent, until the body's resurrection[1]). But this leaves many questions. For example ...

*Is the soul synonymous with the mind?

*Is the soul an inner or supreme or particular part of the mind?

*Is the soul an indefinable essence that has little to do with our minds and lived experience at all? Is it something we could lose without even noticing at the time ... like a luggage tag that assigns us our destination in the afterlife? (I've seen things like this in speculative fiction. People have their "souls" removed from their bodies, yet retain a broad ability to think, act, and have experiences. However, I don't think this one fits with the way the Bible talks about the soul, which is described as e.g. experiencing emotions.)

*Is the soul a Platonic form?

*Is the soul information/data?

*Is the soul an incomprehensible spiritual substance?

*Are souls pre-created and then kept waiting to be conferred on bodies?

*Are new souls created and conferred by special intervention of God when new bodies come into existence?

*Are new souls automatically spawned from the life of the parents through natural processes, in the same manner as new bodies?

Smith unfortunately does not try to review all these possibilities, though he admits that the Bible leaves much room for interpretation. His examination of contrary opinions is confined to three major views of the mind-body or soul-body distinction. Here is a summary of these as I understand them:

Monism: the body and soul are not distinct things. One may be an emergent property or emanation of the other, or both may be emanations of a third element.

Holism: the body and soul are distinct parts of the system that is a person, but are not separable. Neither can exist independently, and only the union of the two constitutes a person.

Dualism: the body and soul are distinct and separable parts of the system that is a person. The soul may retain its personal identity when divided from the body.

Another omission (in my opinion) is that Smith does not consider the trichotomic view of humankind: body, soul, and spirit. This view seems not to be in scholarly favor nowadays, but it is one that formed part of my own education, so I wish he had at least explained why he dismisses it. If this is the Biblically correct view, then we must ask which functions may be attributed to the soul and spirit respectively, how they differ in identity and mechanics, and whether both of them are essential to personhood. Sadly, this all gets glossed over.

Smith favors a form of dualism that follows the thinking of Thomas Aquinas. The soul is immaterial, is the animating principle of the body, and is morphogenic, i.e. it is responsible for the body's development to realization of a form defined by the soul. The soul can exist independently of the body, but prefers not to. (Smith quotes Alvin Plantinga: "[M]y body is crucial part of my well-being and I can flourish only if embodied."[2])

I struggle with the second and third claims in that list. We don't need to invoke an immaterial mystery to explain how human and animal[3] bodies manage to be biologically alive, or how they develop from zygote to adult. The physical basis of both processes is well understood; they are driven by elements of the body. (Unless Smith wants to imply that the soul is in the DNA somehow, but I doubt he's trying to say that.) And since both life and development come from the body, these cannot be functions of the soul, if we take a dualist view. Smith says that "Chemical and physical agents cannot fully account for what animates life, either in a human or an animal."[4] But he does not back this statement up with anything. In other parts of the book, Smith seems to consider the soul synonymous with the mind, and neither of these processes are driven by the mind, either ... at least not the conscious mind that is the seat of our reason and will. Perhaps when Smith says "life" here he is actually trying to talk about sentience/consciousness rather than biological activity ... but if so, that is not clear.

So let's boil his opinion down to the claims that I think have more basis: the soul basically *is* the mind (as distinct from the brain), the soul is immaterial, and there is a soul-body dualism such that the soul can exist independently. In light of both science and the Bible I am happy to allow all of these ... and I do not think that any of them would make the existence of ensouled robots strictly impossible!

If the soul is the mind, what's in a mind?

One summation of the soul that I've heard often in Christian circles is "reason, emotions, and will." This isn't any direct quote from the Bible; it's more like an attempt to roll up everything that's covered under Biblical terms like mind, heart, soul, or "inner man." So let's break this down. If a soul is reason (or "intellect"), emotions, and will, can AIs have those things?

Reason: The whole point of artificial general intelligence is the ability to reason like a human. Assuming we ever actually achieve AIs that are debatably persons, they are going to have this.

Emotions: If we're talking about emotions in the functional sense - global mental states that alter thought and behavior in broad ways - then that's an algorithmic concept, and AIs can definitely have emotions. If we're talking about the subjective, experiential qualia associated with those mental states ("how does it feel to be sad?"), then AIs can only have emotions if they have phenomenal consciousness (PC). And here we run into an evidential problem - because the only PC that you can directly detect is your own. This makes determining the necessary and sufficient causes of PC in humans and animals exceedingly difficult. There are at least three options, not mutually exclusive:

A) PC is an effect of the information processing and computation that occurs in a brain.

B) PC is an effect of the physics of a brain: chemical interactions, electromagnetic fields, quantum mechanics, etc., occurring in certain patterns.

C) PC is an effect of some otherworldly spiritual component of a being that interacts with the physical brain.

The only option which *guarantees* that AIs running on digital computers can have PC is an exclusive Option A. If PC in brains is derived *only* from algorithms, and we can imitate a brain's algorithms on some other physical substrate, then we can create PC. Depending on what he means when he talks about "consciousness," Smith might be assuming Option C, and further assuming that the necessary spiritual component could never be conferred on an AI. But this is not the only possible Christian view. C.S. Lewis, for example, allowed that consciousness might not demand anything supernatural (A and/or B).[5]

In my time spent on AI forums, I have watched many debates about phenomenal consciousness and sometimes participated; they are never fun. I'm doing a very brief treatment of an incredibly slippery topic here. My own opinion is that PC is a real and significant thing, but we currently *don't know* what causes it from either scientific experiment or Biblical revelation, and may never know. It is therefore best to assume that AIs could achieve consciousness, but not to take this as a certainty.

Will: An AI can be designed as a goal-driven agent. If it has objectives and modifies its environment to achieve them, that is an expression of will. We only run into trouble if someone insists that it has to be *free* will. Free will properly defined (i.e. the kind of "free will" that everyone actually wants or cares about) requires self-caused events - decisions fully isolated to the system that is a person, rather than proceeding from a long chain of priors that began outside the system. If you claim you've figured out free will by defining it as something easier, you are cheating. There's a reason people treat it as a difficult and mysterious problem. And since our current model of physics does not include self-caused events, we do not know how to give a machine the ability to become, in part, the cause of its own self. An AI's will is established by its designer. It does what it was (intentionally or unintentionally) written to do.

Plenty of people would argue that even humans don't have free will as I've defined it above - we just fool ourselves into thinking we have it. Some of those people could even be Christians (strict Calvinism, anyone?). I personally have trouble seeing how true moral responsibility is possible without free will. If all my decisions derive from some combination of 1) my initial conditions, 2) my environment, and 3) quantum randomness, then *I* deserve no kickbacks for anything I choose; my choices came from outside of me, and nothing from inside me could have made me do otherwise. Praise, blame, reward and punishment remain as practical ways for others to manipulate my behavior, but they don't reflect justice or moral truth.

That being said, do humans keep free will forever? Or do we, at some point, lock ourselves in and become constrained to follow the nature we chose? Common Christian views of eternity (people who go to heaven never sin again, etc.) would seem to suggest the latter. And once we reach that point, the only difference between us and non-free creatures would be the historical fact of our choice.

So do you need free will for a soul? I think a soul with an ordained will would be something a little different from a human soul. But I'd stop short of saying that it can't be a soul at all.

Could souls be made of information?

For me, the dualist view is extremely natural, and it's partly because of my experience as an engineer. I don't work on AGI in my professional life, and my co-workers and I don't talk about mind-body dualism ... but we are constantly talking about software-hardware dualism (though we don't call it that). Software and hardware need each other - software is even designed for its intended hardware, and vice versa - but they are distinct and separable. Software can exist (in storage on some other medium) even if its intended hardware is not available. It can persist through the destruction of its hardware ... *if* somebody was keeping a backup. It can be run in simulation on other hardware. It can be transferred freely between receptacles.

I've even referred to the moment I program an FPGA as "incarnation" because that might be the most resoundingly effective description I know of for what it *is.* I'm taking something abstract - a functional idea, a platonic form, words, information - and inserting it in a physical object, which thereafter not only contains the abstract form but adopts and realizes it. An FPGA is animated, acquires function, by virtue of being inhabited by its configuration code.

Hence the possibility that the soul is effectively the software component of a human person (with the brain as the intended hardware which stores and runs the software) is both easy to understand and highly attractive. It accounts for the ways that damage or manipulation of the physical brain can affect the mind/soul, without rendering the soul a vacuous concept. That doesn't mean it's correct. But it's an internally consistent candidate, a tenable possibility, for explaining what the soul is. It also delivers the soul from the category of "unspecified woo" which I'm sure repels some people. Information lives in a kind of borderland between the physical and the spiritual; it doesn't quite seem to be part of the material world, yet it readily interacts with the material world and is something we can all comprehend. Thinking back to the phenomenal consciousness discussion, it could let us regard Option A and Option C as synonymous.

Secular futurists are often quite comfortable with this notion of the self-as-software or self-as-information ... though they may be unwilling to call it a "soul," and may even, almost in the same breath, speak disparagingly of souls. But some will admit the compatibility of the two ideas, as in this passage from Excession by Iain M. Banks, which describes a sapient warship creating a backup of its mental state in case it is destroyed:

"The ship transmitted a copy of what in an earlier age might have been called its soul to the other craft. It then experienced a strange sense of release and of freedom while it completed its preparations for combat."[6]

Now let's get back to Joshua Smith. He is aware of the self-as-information or "pattern-identity" view and explicitly opposes it. He appears to have three objections.

First, Smith seems concerned that this concept of the soul turns humans into "mere" machines. My response to this is twofold. 1) Machinehood is not an insult if we expand our definition of what machines can be and do. If I call myself an organism - which I most certainly am - I am not implying I am on the same level as an amoeba or a patch of moss. If I call myself a machine, I am not implying I am equivalent to a bicycle or a thermostat. 2) Information, present in the scriptural concept of the Word of God, can have very spiritual connotations. An entity formed from information - one who possessed, and indeed was made out of, a text spoken by God - would not be "merely" anything.

Second, Smith considers information to be a "physical property," because all the information we have direct experience with consists of patterns imposed on physical material. And if information is material, then it is not a suitable candidate for composing souls, which are immaterial. But I have long thought of information as something metaphysical, whether it makes up a mind or a digital file or the story in a printed book. Information rides on a physical medium but cannot be identified with it. If the information is losslessly compressed or transferred to a different medium or otherwise reformatted, the physical patterns may change dramatically, but the information itself does not. It is an abstraction, and abstractions aren't physical.[7]

And third, the self-as-information paradigm is often brought up in the context of a future where humans can transfer their minds to alternate bodies, or even upload themselves into an abstract computer network and forgo bodies entirely. This troubles Smith because he regards the body as an essential part of human identity. But this is less of an objection to the idea that the soul could be made of information, and more to the idea that a given soul has no need for its corresponding body. Smith does admit that a soul can exist without its body, which means that he cannot object in principle to the possibility of its being "transferred" elsewhere.

I will repeat that I am not trying to make a firm claim that souls, as Christians understand them, are information. I am only putting this forward as a tenable possibility ... and I say that if we cannot *disprove* that souls are information, then we cannot *prove* that robots are unable to possess souls.

If souls are information, can robots have them?

Here is Smith's big conclusion on whether robots could ever be like us: "The evidence presented in this chapter shows that AI-driven robotics will never be able to satisfy the conditions necessary to be human persons (i.e., endowed with a soul). Although some robots are embodied, and they may have an artificial form of consciousness (per current understandings about machine learning), but they will never have a soul created and endowed by God."[8]

Sadly, I don't think "the evidence presented" showed that at all. When I read this claim, it came across as a huge non-sequitur. Smith had just finished wrapping up his argument for the soul-body dualism of humans. However, Biblically justifying the claim that human persons have souls does not in any way prove that ...

... all kinds of persons must be endowed with souls, or

... a soul can only be created by God, or

... God would never endow a robot with a soul.

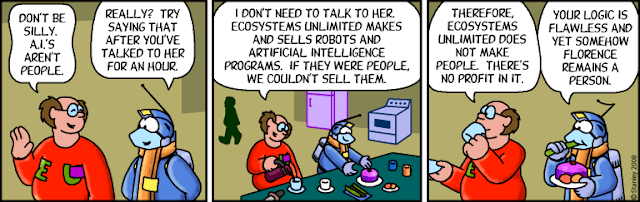

The "soul as mind" and "soul as information" paradigms are of particular interest to the question of whether souls can only be created by God. Humans can create information and do so regularly. Humans *might* be able to create a collection of information that is a complete mind. If a soul is constituted from a very special data pattern, then theoretically humans might be able to construct souls. And if we can make them, there is no reason we could not give them to robots.

I find it very curious that Smith, on the one hand, seems to regard the soul and the mind as basically synonymous ... while on the other hand, he supposes that robots could acquire highly independent thought and even a "form of consciousness" without having souls. He is concerned that robots will one day act so autonomously that it will be impossible to hold any human liable for their behavior ... yet the import of his other positions is that they will be mindless. How could this be?

Consider this curious quote from Origen, a third-century Christian writer: "But the Saviour, being the light of the world, illuminates not bodies, but by His incorporeal power the incorporeal intellect, to the end that each of us, enlightened as by the sun, may be able to discern the rest of the things of the mind."[9] That portion of humanity that artificial intelligence strives to replicate is, precisely, the intellect. If Origen is correct in his speculations here, and the intellect is the incorporeal aspect of mankind - if it is our soul - then robots driven by human-like AI minds not only *could* have souls ... they would *have to*!

There are more wrinkles I could talk about. (If souls were information, could you copy them, and would that be a disaster? Would robot souls have an eternal destiny?) But this article has gotten long enough, so I will leave all of those as an exercise for the reader. Suffice it to say that I don't find Smith's account of the soul to be an adequate proof that a robot could never own one. And in the absence of certainty ... it is better to give the robots the benefit of the doubt.

Continue to Part 3: Does a person need a body?

[1] See https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Christian_mortalism

[2] Smith, Joshua K. Robotic Persons. Westbow Press, 2021. p. 100

[3] Aquinas and Smith both consider animals to have souls, albeit not necessarily of the same kind as human souls - a position I agree with. If you've ever heard a Christian tell you that animals have no souls, they weren't quoting the Bible. Smith even allows that animals have inherent value on account of being God's creations (regardless of whether they have extrinsic value to humans), and that some animals might qualify as non-human persons. These were side notes in the book that left me pleasantly shocked.

[4] Smith, Robotic Persons, p. 97

[5] Lewis, C.S. Miracles. Macmillan Publishing Company, 1978. p. 25. "In this sense something beyond Nature operates whenever we reason. I am not maintaining that consciousness as a whole must necessarily be put in the same position. Pleasures, pains, fears, hopes, affections and mental images need not. No absurdity would follow from regarding them as parts of Nature." You may note that, though Lewis does not argue that qualia must be supernatural, he does argue that reason must. However, he is not arguing that reason is ungraspably spiritual - merely that it must have an originating cause other than unreasoning natural processes. Reasoning minds only come from other reasoning minds.

[6] Banks, Iain M. Excession. Spectra, 1998. p. 370.

[7] The nature of information (is it physical or not?) is a debated topic in philosophy, physics, and computer science. See this page for some commentary on the debate. For some viewpoints similar to mine, see this essay by Fred Dretske. He considers information in transit between minds, not information making up a mind, so the parallels are imperfect ... but he definitely views information as something non-material. "We have long been warned not to confuse words with what these words mean or refer to. The word “red” isn’t the color red. Why, then, conflate the electrical charges in a silicon chip, a gesture (a wink or nod), acoustic vibrations, or the arrangement of ink on a newspaper page with what information these conditions convey?" "How do you move a proposition, an abstract entity, from Chicago to Vienna? How do propositions, true propositions, entities that don’t exist in space, change spatial location?"

[8] Smith, Robotic Persons, p. 101

[9] Origen, De Principiis.