"You listening, Bog? is a computer one of Your creatures?"

- from The Moon is a Harsh Mistress, by Robert A. Heinlein

Many things that fall under the banner of "artificial intelligence" nowadays are merely passive tools for data mining or generation. But looming in the background of the field, one may still notice the greater dreams of science fiction: complete artificial minds, self-contained entities with something like agency and personality. And whenever these are imagined, certain thorny questions make themselves evident. Is everything with apparent personality a person? Would sufficiently advanced AIs deserve to have their safety and autonomy protected? Might they merit moral or legal rights?

There is, further, a stereotype about how religious people would answer such a question: with an emphatic "no." The most blatant example I know of appears in the video game Stellaris. The player manages an interstellar civilization which will (probably) develop sapient AI. If the player opts for a "spiritualist" civilization - i.e. one whose dominant culture promotes belief in the supernatural - they will *never* be able to give AIs full citizens' rights. The reason is obvious with a little thought: spiritualist people could be expected to believe that they contain some spiritual component, and they might believe that this would be impossible to give to machines, constructed by manipulating mere matter.

And yet, it always got under my skin a bit. Because one can also imagine spiritualist people having *other* views. Shackling them to an approach that at least has a chance of being the less magnanimous one ... well, that seems unmerited.

Returning to the real world, I suppose I never expected to see a serious treatment of how a particular religious belief might interact with opinions on AI rights. But following quirky academics on Twitter yields marvelous things, and last year I discovered a new book: Robotic Persons, by Joshua K. Smith. It purported to be "a fascinating contribution to the study of human-robot interaction, from a Christian Evangelical perspective,"[1] and it even appeared to be robot rights positive.

So I was excited to read and review it: both because this is the exact sort of discourse that's relevant to an AI blog, and because I'm the book's target audience. Ah ... yup, if you hadn't guessed, I'm an evangelical Christian. Hi. *waves nervously*

I'm a unique wrinkle in that audience, though, because I'm working on robots and AI myself. I get the feeling that Smith didn't quite anticipate this. He seems to be urging his readers to approach the robotics community and offer ethical input. He does not speak as if any of us *are* the robotics community. This isn't a book about the godly way to design robots; it's a book about how to react to a secular world that is already doing it. So maybe I can fill in some holes ... or just disagree with him vehemently. We will see!

Naturally these are controversial topics, and I have a feeling that my opinions are going to seem weird (crazy even?) to both the materialist and spiritualist sides of my audience. But it's too interesting not to talk about, soooo here we go ...

|

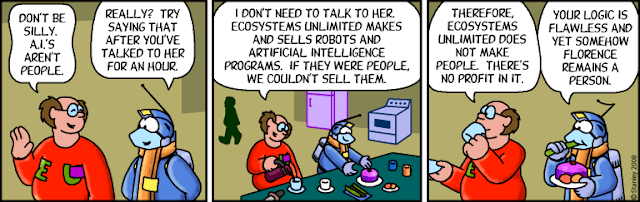

| Comic from Freefall by Mark Stanley. |

Before I get to the book report, I'd like to lay out my own perspective on AI rights, just so everyone knows what sort of bias I brought to my reading. This is admittedly somewhat tentative, since debate on the issue is still evolving and I'm sure there is much more I could read.

1. The precautionary principle should rule here. If something is to all appearances a person, and there's a side of the debate that says it is a person, you really ought to treat it like a person -- even if you think you have good philosophical reasons for believing it isn't. Err on the side of extending more rights to more potential individuals. The cost of being wrong is generally larger if you don't.

2. The interaction between humans and advanced AIs is best viewed as a creator-creation *relationship* and should reflect our ideal vision of what such a relationship could be. We should treat our creations the way we would want our creator to treat us. And in addition to any inherent value they might have, AIs that are loved by their creators have derived value. To disrespect an AI is to disrespect the human(s) who made it.

3. There are two parts to the issue: "what sort of personal attitude should Christians hold toward AIs" and "what public policies regarding AIs should Christians advocate for." Specific doctrines about souls, the image of God, and whatnot are relevant to the first one. Opinions about the second one need to be based on more universal premises (given that we don't live in a theocracy and many of us don't want to).

Courtesy of the book, I found out that the Ethics and Religious Liberty Commission (a project of the Southern Baptist Convention) recently released an "Evangelical Statement of Principles" on artificial intelligence. The statement harbors some optimism about AI's use as a tool to benefit humanity, but also grabs onto the idea of rights with jealous hands. The first article demands that no form of technology ever "be assigned a level of human identity, worth, dignity, or moral agency."[2]

But what does Joshua Smith think? The short version is that he does support some robot rights, but not in a way that I find complete or satisfying. I plan to do an overview here, then go into some of the most interesting issues more deeply in further blogs.

Smith begins with a survey of what he calls "robot futurism," or speculations about the trajectory of robot development and how it will affect humanity. He moves into a study of what the Christian concept of personhood ought to be. Then he draws upon these theories to consider the practical concerns that might attend future robotics, and the legal frameworks that might help address them.

The book is relatively short and easy to digest. If you have enough philosophy background to know words like "teleology" and "monism," it should be pretty understandable. I finished it in under ten hours. Unfortunately, this brevity comes at the expense of depth. Tragically absent elements include the following:

*A thorough discussion of the hard problem of consciousness

*An explicit examination of sentiocentric ethics and how consciousness - as distinct from intelligence or social acumen - is (or isn't) involved in personhood and natural rights

*Consideration of the tripartite view of humanity (body/soul/spirit), in addition to dualist (body/mind or body/soul) views

*An examination of proposals for how (immaterial) souls and (material) brains might interact

But there's still a lot here worth talking about.

Smith is refreshingly willing to acknowledge how ambiguous the Bible is on several pertinent topics -- such as what exactly the "image of God" consists of, or how to define a "person." But even after admitting just how much we haven't been told, he still comes out certain that robots can't be true persons or have natural rights, because something something they don't have souls. I'm being a little flippant here, but this is a weak claim on his part; I don't think he came anywhere near refuting the possibility of robots having souls. What even *are* souls? How do humans get them? Why *shouldn't* a robot have one? (See the followup essay on souls.)

Though he does not regard any robot as a natural person, Smith is of the opinion that robots meeting certain criteria should be *legal* persons, much as corporations can be. Legal personhood is less of a moral statement and more of a practical convenience, and this fits Smith's main goal - which is to protect *humans* from possible abuses by robots. A robot designated as a legal person could be given defined privileges and responsibilities, held liable for its actions, and punished for crimes. Present-day law would hold a robot's creator or operator responsible for any infractions, but in the future robots may become so independent that no liable human can be found, and the only way to mitigate bad robot behavior will be to address it directly. Limited liability would also encourage innovation by insulating robot developers from blame for unpredictable outcomes.

Legal personhood could also offer some protections to the robots themselves, of necessity. Discipline for bad behavior has limited effectiveness unless opposed by tolerance for good behavior. A robot with legal rights would have an incentive to maintain its own interests by obeying the law. (For instance, Smith suggests that robots could be enabled to own property for the sole purpose of making fines and forfeitures an effective way to punish them!) Giving rights to robots might also undercut the arguments of those who would try to deny rights to the more vulnerable members of the human community.

This is all better than nothing, and Smith is granting quite a bit more than I think some Christians would. Still, he makes it pretty clear that any benefits to the robots are an afterthought. He's worried about human safety and dignity, and his consideration of robots as legal "persons" is an oblique way of addressing these worries. He does not think that robots should ever become full citizens; they should, for instance, not be permitted to vote. So he would see the creation of an underclass: entities who are not acknowledged as true persons, yet are so "person-like" that they are treated as persons in selective ways. I hope you can see what's uncomfortable about this.

|

| I'm leaning heavily on these Freefall cartoons, but they just illustrate things so well sometimes. Freefall is by Mark Stanley. |

Smith's focus on human rights is also confined to the interests of those who might be harmed by robots. He does not consider the interests of those who create robots (beyond his thoughts about limitation of liability), or assess whether robots might merit derived rights based on their creators' investment in them. Part of the trouble here is that he never considers robot creation as a personal act of relationship. All the robots Smith talks about are built by corporations for a practical purpose, and the notion of any developer expressing love toward their work appears not to have entered his mind.

Lastly, Smith - rather strangely - views embodiment as a necessity for personhood (natural *or* legal). So abstract AI programs don't even get the grudging respect that he grants to robots, no matter what their intelligence level, social capacity, or ability to be moral agents. Smith seems anxious to avoid the Gnostic error of devaluing or condemning the human body, but in his efforts he ends up devaluing the mind instead. (See the followup essay on bodies.)

Much of the remaining discussion is about the practical regulation of commercial robotics. While admittedly important, this part of the book was less interesting to me. I do not really plan on commercializing my work and deploying it widely to replace humans in the workforce. Nor do I plan on doing work for the military, or making sexbots. (These are the three potential applications that most concern Smith.) But this is where Smith makes his clearest calls to action, so in some ways it's the heart of the book. I tried to write up a brief summary of his positions and my responses ... and it turned into yet another whole blog entry.

Smith has a seminary education, and his grasp of the Bible reflects this; artificial intelligence is the foreign field to him. He has clearly made an effort to browse the classic AI literature and inform himself, and his understanding of the technology is usually sound. Yet there were still a couple of unfortunate moments when I wanted to yell, "This man has no idea what he's talking about!"

One of these came when Smith was complaining against Moravec's opinions. "Reducing the value of a human to computational power shows little concern for ... the non-computational aspects of life in which humans find dignity and value, such as art, philosophy, and literature."[3] But an AI researcher would simply contend that art appreciation, philosophy, and literature are also computational! Smith appears to be associating computation with something like logic or mathematics, and denying its ability to produce more "subjective" judgments and behaviors. He does it again in the last chapter, when he says "[The moral reasoning needed for ]War is not reducible to mathematical computation."[4] These are unfounded assumptions, and I think they reveal a lack of awareness of the versatility of algorithms. Smith's inability to imagine how such things might be computed does not prove the impossibility of doing so.

My other facepalm moment came after Smith quoted Brooks, who talks about human empathy for fellow creatures. Smith then says, "[Brooks'] logic here goes against the grain of earlier futurists, who held ... that humans are merely complex and sophisticated machines responding to computation and predetermined programming. Futurists have argued the humans-as-machines view for quite some time, yet in reality, humans do not treat other humans like mere machines ..."[5]

Smith appears to be confusing the physical materialist position that "all human behavior can be completely explained by physical processes, making humans sophisticated biological machines" with the nihilist position that "a human has no greater moral worth than a pump or a bicycle." The former does not always lead to the latter. If Smith were to talk to some of the people I know who hold the "humans-as-machines" view, he would find that they believe in empathy and natural rights and the whole ball of wax. So despite my own reservations about this view, I think he characterizes it unfairly.

I am glad that Joshua Smith wrote this book. Despite all of my complaints above, I appreciate the attempt to put something out into the obscure intersection of robotics and religion. It was a vehicle for issues seldom talked about, and a great catalyst to thought even when I disagreed with it. But it has a number of inadequacies, and more books on the topic need to be written.[6]

Until the next cycle,

Jenny

Review Part 2: Maybe souls aren't as elusive as we thought

Review Part 3: Does a person need a body?

Review Part 4: To bear an image

Review Part 5: What to do with all these robots?

[1] Smith, Joshua K. Robotic Persons. Westbow Press, 2021. From the Foreword by Jacob Turner.

[2] https://slate.com/technology/2019/04/southern-baptist-convention-artificial-intelligence-evangelical-statement-principles.html

[3] Smith, Robotic Persons, p. 31.

[4] Smith, Robotic Persons, p. 182.

[5] Smith, Robotic Persons, p. 38.

[6] Smith has recently come out with a new book called Robot Theology. I haven't read it yet.

Hah! I bumped the back button on my mouse and lost everything. Ah, well.

ReplyDeleteLet me start by stating (hopefully reaffirming) that I'm so happy I met you.

Second, my thoughts align well enough that there's little to add except I saw a through line here regarding the nature of consciousness being unexplored.

The sort of sine qua non here is that either the biological processes in our brain produce an emergent consciousness that ceases when the biological processes do, or if there's something that endures or is otherwise external to the process. I get why it's not discussed. It's existentially terrifying. There are also theological components to the answer, some of which are more key tenets than others.

There are logical fallacies in this as well. If one denies the soul, so they deny the afterlife and/or God. I get the logic, but I think that's a pretty large leap. I feel it's mostly reactionary, as this question is so fundamental that it's terrifying. The abyss stares back. Find me someone who can really consider their own consciousness, and thus their own mortality, and conclude that when it ends, it ends, without a feeling of dread and I'll show you someone in denial. It really does provide comfort to believe that there is something, anything, beyond raw biology.

I also find it amusing how my musings on AI on Lunatic Labs was before I saw you had a new post here. It's neat to see how we all draw water from the same well. Particularly the empathy thing. How strange.

Anyway, if you don't want to clutter up your blog but still want to discuss this, I can shoot you my e-mail if you want to talk off-blog. Some people enjoy public discussion, others don't. I provide options. ;)

Aw. Michael. Really? I'm very happy I met you too.

DeleteI thought this one might pique your interest and I was kinda hoping you'd comment on it. Talk about anything you like here; it's a contribution, not clutter.

The funny thing is that Smith (in the book) seems critical of the way some futurists skate over the mysteries of consciousness, but he never really settles down and devotes page time to it himself. You can find bits of his opinions sprinkled through the text, and discover that he thinks consciousness is difficult to figure out (I agree, but I wish he'd done more to explain why), and that this obscurity leaves room for an otherworldly soul to be at least partly responsible.

On AI forums, consciousness is a topic that actually seems to come up often - it's a known mystery, and a lot of people want to believe they've got the answer. Mostly these are secular people arguing that they can, in fact, build a fully conscious machine. These particular discussions seem not so much terrifying as ... fruitless. Frustrating. For one thing, "consciousness" is a multi-faceted concept, and people happily confuse the different facets. It's hard to even be sure that everyone is talking about the same thing. Get over that hump, and sometimes they'll try to dismiss the most difficult part as unimportant.

I'm going to say more about it in one of the detailed blogs, which I think I'm putting up in a day or two.

Neat! Looking forward to it.

DeleteAs a meta about metadebate . . . or something . . . we (Humanity) have a big problem with "I don't know what the answer is, but I know that's wrong." Consciousness is . . . messy. The terminology gets cut so fine and is used with so little regard for nuance that it's almost frightening to ponder the scope of the debate.

Without insult, Dunning-Krueger explains a lot of neophytes. They don't know how much they don't know, so of course their idea has never been thought of and is the magic bullet. On the other end, many specialists learned from the same sources and run the same doctrine, so sometimes a radical idea with no regard to the state of the art can inspire a jump to a new branch of the discipline.

Or it can be the Polywell reactor, which last I heard was a math error. :( At least I never managed to source superconductors.

Right, consciousness. Is that synonymous with sentience? Does it have to know it's alive? Some birds, dogs, dolphins, and many others have shown they understand the "self" but is that a requirement? Beavers build dams, are they tool users? Crows. Oh my, crows. Do they have languages and funerals or are we projecting? They understand, at the most basic level, trade and gift giving. I'd be floored by any AI that did half of what a crow can do.

That's where we get practical measurements such as the Turing Test. I just figure if it can make a pun, it's conscious. :D

That's only kind of a joke. Think about what goes into a pun. It's nonlinearity and abstract thinking.

I've always seen the fundamental break for the human condition is imagination and the ability to make a plan that extends beyond our individual lifespan. But that's still not consciousness.

Fiction is full of a robot dreaming of freedom or asking if it has a soul, and being immediately destroyed in terror, but even that's so narrow.

We have pareidolia, mental images (well, most of the rest of you do ;) ) and so many ancillary things that make us us, but is that required for consciousness?

Yeah, no, you nailed it. Fruitless.

It's a philosophical and biological question that can only be answered from the inside. How can you measure a system from the inside? If the act of observation changes the results, how could we even find the edge? How do you see the edge of your vision?

At some point, I feel like pointing at the DSM and a law library and saying "that's less maddening." So much is codified, and consciousness is so fundamental . . .

Around and around I go.

If an AI can explain consciousness to me in a way that seems accurate, I'll draw the line there.

A problem well defined is a problem half solved. This is just an indicator that the question is far, far too broad. This is like asking to solve death.

Actually, looking at negative space and going on a strange journey I can't recall, I don't have a definition, but I have a pithy one liner!

DeleteConsciousness is hardware providing two incompatible desires and software choosing a third option that's still rational.

Pithy and useless! Perfect philosophy! We know you have your choice of semi-lucid hermits, and appreciate you choosing us. ;)

Imagine being deep in a fever dream. Your rational mind is basically shut down, but sensations from your sick body are still present to you, and you're very uncomfortable. Your mind is probably too murky to even think about this; you can't reflexively examine your own state and (mentally) tell yourself, "I am suffering." But you are. You're having a lived experience.

DeleteTo me, that sort of thing is the beginning of consciousness, the lowest level: experienced sensation or feeling, without thought. It gets more diverse and layered in higher minds that are fully awake; thoughts and self-awareness introduce their own varieties of experience. But that's the entry point, and the mystery. What is it about brains that makes them have experiences at all? And if experiences can come without thoughts, are thoughts always experienced?

Of course, when I broached this to one of my compatriots on the AI forum, he insisted that a person in that fever state wasn't really conscious ... at least not in the important way. I'm not certain, but I think he even implied that if you couldn't have thoughts about an experience, you didn't really experience it. If you can't conceptualize "I hurt" and "I enjoy," then you don't hurt or enjoy; the qualia by themselves count for nothing. Which to me just sounds ridiculous ... like I said, these talks tend to be fruitless.

I think you have one of the important points, though, which is that consciousness can only really be seen from the inside. I know what mine is; you know what yours is. But how can I know yours? I can't climb inside your head and have your experiences with you. You can try to communicate, and I can think, "Well if *I* said that, *I* would be feeling ..." But that's a reasonable inference, not a direct observation. I can never really be sure what it feels like to be you, much less what it feels like to be a dog, a bird, or a spider.

I also like that you called it fundamental. Subjective experience is subjective experience in the same sort of way that time is time or energy is energy; it's hard to define in terms of something else. So people either get what I'm talking about, or they don't. Very frustrating.

I like the fever dream analogy. It brings up so many tangential questions. If I have consciousness (hopefully so stipulated) then one could argue I continue to be a conscious creature during the fever dream, just in an altered mental state. We can argue, for our definitions, even dreaming is a conscious action. By the definitions of experience and conceptualization it qualifies, despite being utterly disconnected from the world.

DeleteMore than that, we start asking questions about if once you cross a threshold you can fall beneath and still have consciousness, assuming you can return. Are you suddenly "not" during that gap? Is blinding pain still consciousness?

I'm not going to get into the butterfly dreaming he's a man stuff, but when I drive, I don't think of my hands and feet using the controls, I think of controlling the vehicle directly. Given how the brain can adapt so readily, if I woke up with new hardware, could that become as natural as anything else? We have trouble learning new letter sounds as we age, and nerve damage is generally critical, but Pistorius became an Olympic level runner with replacement lower legs. Slight aside, but it's always in my brain.

I can see how it would be frustrating, especially if new people keep posing the same questions. Here's a personal favorite analogy of mine: color.

People always ask me what color something looks like, but only once. If we both look at an apple, we see very different things. If you ask what color I see, I say red. Because we have stipulated that the color on that apple is red. We can do funny stuff with wavelengths of light, but as far as vision goes, the apple is red, no matter what we see. Red is not an apple.

There is no way to describe red except referring to other colors. You can call colors "warm" and "cool" only because those terms are linked to known colors. It is utterly impossible to explain a color except as a reference to a common external standard.

I think there's some merit to exploring the bounds by looking at fever dreams, regular dreams, babies, and those with altered mental states. I can remember glimpses of my very early life. I think the oldest is taking oral medicine in the kitchen of our first house. I'd think I was older than I was, except I know the new house was when I was very, very young. (Looked it up, I was 4 when we built the new place and remember the construction being . . . later than this memory?) I recall clearly the layout of the room, the little dosing spoon, how small I am . . . but so little else. Except: I knew I wanted to open my mouth, but it wouldn't open. I was actively fighting my body to open my mouth, and it reminds me of when I needed to do something painful, like for blood sugar tests. The body refuses to act and needs to be overridden, thus my benchmark.

It's a big discussion. Spent too much time thinking about it. Probably going to spend more. ;)

Oh, one more thing, a line introduced to me by Sid Meier's Alpha Centari but appropriate to the conversation:

ReplyDelete"Companions the creator seeks, not corpses, not herds and believers. Fellow creators the creator seeks—those who write new values on new tablets. Companions the creator seeks, and fellow harvesters; for everything about him is ripe for the harvest."

– Friedrich Nietzsche, "Thus Spoke Zarathustra"

I don't think I'd heard that one before. That's good. As a return gift, here is a Tolkien quote, from his lecture "On Fairy Stories." He's talking about writing, but it works for many forms of creation of course.

Delete"Fantasy remains a human right: we make in our measure and in our derivative mode, because we are made: and not only made, but made in the image and likeness of a Maker."

Alright, there is a lot here and it's very interesting.

ReplyDeleteFirst of all I love these type of blogs from people who are working on some idea, they are like lone houses far from the city center. And the owner keeps improving it and brings interesting things inside even though there are not as many visitors. And you're happy when you've found one because you know there's going to be something interesting and new. (hopefully this is not to weird to be a compliment)

I think consciousness may be something that appears when all necessary conditions are created, like an electromagnetic field. That in turn will mean that we all have "the same consciousness", and what makes us different is our memories. But that would also mean that upon death memories are most likely lost. And it's interesting, we don't perceive people with memory loss as dead, but they are practically dead to us personally.

I think a lot of interesting discoveries are waiting there. People can loose memory after some accidents and not even remember you anymore and in some severe cases may forget everything about themselves as well and start their life "again", in this case they would be practically dead in relation to you, be a complete stranger. And they could go on living but now being a different person compared to that before the accident. And to me that hints that consciousness may be something different and independent from memory and intelligence. Although I've got away from the topic, I don't think robots couldn't aquire consciousness, but some special hardware may be required. What do you think about that?

By the way, I have an idea and some 3d models already, to get that spider life experience. It would be also a mouse experience in some way. But that may or may not happen later as I don't have the ability to get all the parts needed right now and also there is this probably not good habit of wanting to do a lot of projects that can slow down the process. But if everything will be good I will know, whom to invite as a tester :D

No, that is not a weird compliment at all. I quite like it. Thank you!

Delete"I think consciousness may be something that appears when all necessary conditions are created, like an electromagnetic field."

That's the idea of consciousness being an emergent property - it isn't synonymous with any algorithmic or physical process, but maybe it arises from them. I could see this being the case. The hard part is, how do we figure out what those necessary conditions are?

"And to me that hints that consciousness may be something different and independent from memory and intelligence."

I absolutely agree that it's different. I think of (phenomenal) consciousness and intelligence as orthogonal concepts; one could, at least theoretically, have intelligence without consciousness, and one could have consciousness with little or no intelligence. See my previous comment about the fever dream state; the core aspect of consciousness is the ability to experience something, and one can experience sensations without really thinking about them. And although a person's history is part of what defines them, I agree that continuity of consciousness is a different idea. If I had to choose between 1) losing all my episodic memory and effectively starting life over, and 2) losing my experiential existence forever, but preserving all memories and transferring them to someone else who would continue my projects - I would pick #1.

I still don't find myself in a position to entirely discount the computational theory of mind, and the possibility that consciousness emerges from certain kinds of information processing. But I'm also open to the other possibility that consciousness would demand hardware that reproduces certain physics. I think it's a truly difficult problem, and at this stage, anyone who's too confident that they know where consciousness comes from is overselling their position.

And good luck with your own project! I fully understand the problem of wanting to do too much at once haha.

Delete